August 25, 2017Huffingtonpost – Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, Contributor – Human rights record has deteriorated markedly in Iran according to human rights organizations including Amnesty International.

August 25, 2017Huffingtonpost – Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, Contributor – Human rights record has deteriorated markedly in Iran according to human rights organizations including Amnesty International.

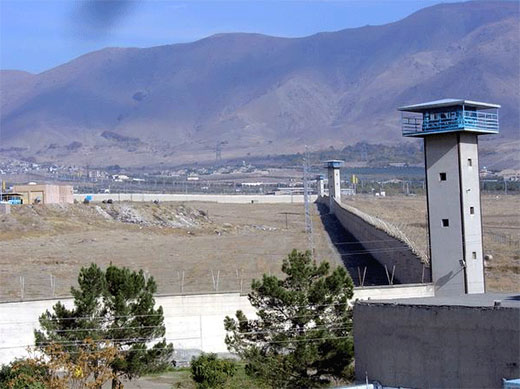

For example, most recently, on July 30, inmates in Ward 4, Hall 12 of Iran’s Gohardasht (Rajai Shahr) Prison were made subject to a violent and unexplained raid that led to more than 50 persons being transferred to Hall 10, where conditions and treatment are even worse than the prisoners had been experiencing up to that time. Hall 10 had been newly renovated ahead of the raid, apparently with the explicit intention of putting more pressure on the prisoners of conscience that the Iranian government was planning to transfer there. In their new surroundings, the prisoners are subject to 24-hour video and audio surveillance, even inside private cells and bathrooms. Windows have been coveredover with metal sheeting, thereby reducing airflow during summer in a facility that was already known for its inhuman and unhygienic conditions. In additional, the raid saw the confiscation or outright theft of virtually all of the inmates’ personal belongings, including prescription medications. Since then, prison authorities have denied the prisoners access to medical treatment and have even blocked the delivery of expensive medications purchased for them by families outside the prison.

According to Amnesty International, withholding medical treatment is a well-established tactic utilized by Iranian authorities to exert pressure upon political prisoners, especially those who continue activism from inside the nation’s jails or strive to expose the conditions that political prisoners and other detainees face. The former residents of Hall 12 certainly fit this description, as evidenced by their response to the raid and worsening conditions. Despite the fact that their newfound stress and lack of sanitation already threatened to have a severe impact on their health, more than a dozen of the raid’s victims immediately organized a hunger strike and declared that the protest would continue until they were transferred back to their former-surroundings and had their belongings returned to them.

In subsequent days, several of this initial group’s cell mates joined them, and at last count, 22 detainees were participating in the hunger strike, the vast majority of whom are serving sentences for political crimes like criticizing the government’s policies or supporting the country’s leading banned opposition group, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran. The core group of hunger strikers has been starving themselves for approximately a month now, and their health conditions have predictably deteriorated. Heart, kidney, and lung ailments have been reported, among other health problems in Iran’s prisons, and the prisoners appear to be rapidly approaching the point at which they may start dying as a result of their protest. Nonetheless, neither the Gohardasht authorities nor the Iranian judiciary have shown any sign of responding to their demands or publicly addressing the severity of the crisis. What is much worse, though, is the fact that the international community has not proven to be much more attentive to the hunger strikers’ dire circumstances.

Notwithstanding calls to action by such human rights groups as Amnesty International, there has been virtually no push by Western governments or the United Nations to put pressure on the Iranian regime to save the lives of the Gohardasht inmates. This is particularly disappointing in light of the recent shifts in Western policies toward Iran, which come after years of conciliation and neglect for human rights while the United States and its allies focused their attention narrowly on the nuclear issue and prospective trade deals. During that time, various human rights activists rightly criticized the world community for putting certain matters of Iran policy on the back burner even though they had an absolutely immediate impact on the lives and safety of potentially millions of Iranian citizens. It has been widely reported that Tehran has been cracking down with escalating intensity on journalists, activists, and other undesirables, and thus swelling the ranks of its political prisoners.

The Gohardasht raid is a clear indication that this trend is still ongoing, but the resulting hunger strikes are an equally clear sign that Iranians as a whole have not capitulated to the pressure yet. Unfortunately, in absence of a coordinated international response, this situation also promises to be a sign that for all their resilience in the face of violent repression, the Iranian people have precious little outside support that they can rely on. Every global policymaker and every prominent human rights activist has a responsibility to prove this conclusion wrong. Organizations like the National Council of Resistance of Iran have vigorously responded to the hunger strikes by calling for the United Nations high commissioner on human rights and the special rapporteurs on torture and on human rights in Iran to issue public statements and initiate a coordinated strategy that will impose serious penalties on the Iranian government if it does not address the plight of the Gohardasht hunger strikers. Some organizations that claim to be advocate of promoting Iran’s situation and Iranian people’s rights have ignored the issue and human rights violations.

There is desperate need for international inquiries not only into this but also into various other human rights crisis throughout the Islamic Republic. In fact, while the Gohardasht situation is particularly urgent, once an adequate international response is made, it should only serve as the template for many more such inquiries, some of them into human rights abuses that are happening at this very moment and some of them into crimes against humanity that no one in the mullahs’ establishment has ever answered for. In the summer of 1988, some 30,000 political prisoners were hanged simply for suspected loyalties to anti-theocratic resistance groups, mainly the PMOI. The incident was largely ignored in Western media, and despite a handful of statements over the years, no serious inquiry has been launched to identify the locations of the secretly buried victims or to pursue charges against those responsible, many of whom retain positions of influence to this day.

Although 1988 marked the single worst act of repression against Iran’s population of political prisoners, the Gohardasht hunger strikes highlight the fact that the overall pattern of repression remains unchanged, while the ruling clerical establishment remains as indifferent to human suffering as it ever has been.

It goes without saying that the international community as a whole is better than this; but that community must act accordingly, to protect and promote human rights, and intervene when Iran’s political violence threatens to claim new victims.