A protester in Shiraz, November 2019Middle East Images / Redux

Repression Won’t Solve the Deeper Problems Bringing Iranians to the Streets

December 5, 2019 -Foreign Affairs -By Mohammad Ali Kadivar, Saber Khani, and Abolfazl Sotoudeh

A wave of protest swept across Iran last week. The government had abruptly hiked gas prices in order to offset its budget deficit at a time of high inflation and negative economic growth. Angry protesters clashed with security forces, set government buildings and banks on fire, and blocked roads. The government responded with an iron fist, killing more than 200 protesters, arresting thousands, and shutting down the Internet across the country for about a week.

In a country where anti-government demonstrations are not allowed, widespread protests with an explicit anti-regime tone are significant. But to understand the meaning of these protests—to know what motivated protesters and why—is exceedingly difficult, given the restrictions on free expression and international communication that currently prevail in Iran. The identities and agendas of the protesters matter for their own sake. They also matter because Iran is a country eternally in the spotlight and often misunderstood.

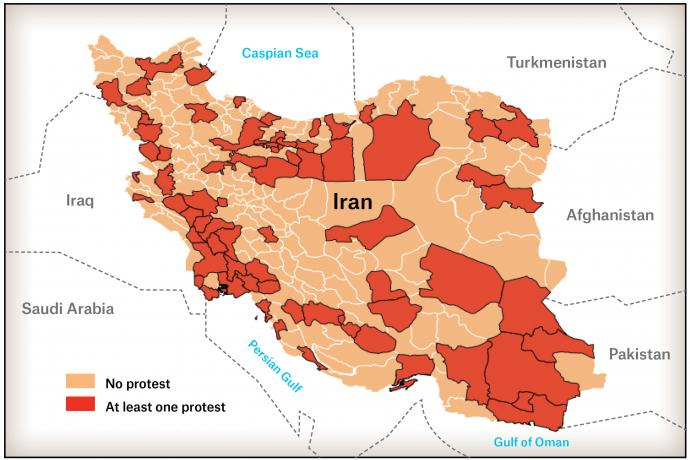

It is not possible to question every protester or to reliably survey public opinion. But meaningful data about Iran do exist and can be fruitfully matched to the map of protests. We identified the counties that witnessed at least one day of protest, based on the videos that protesters uploaded to both domestic and foreign websites. Then we examined socioeconomic and political data for those counties. Using a simple logistic regression, we were able to estimate the effect of such factors as electoral participation, development, wealth, population size, and unemployment rates on the outbreak of protest.

Our study shows that the current wave of protest is geographically widespread and most likely motivated by more than acute economic pain. We found that 20.5 percent of all Iranian counties had at least one day of protest in this wave (89 out of 429). Economic grievances sparked the initial surge of action, but once the protests began, they appeared to activate deeper, preexisting dissatisfactions with the Islamic Republic as a whole. In fact, our results indicate that while the regime gained support following recent elections, specifically the 2017 presidential election, that support has since eroded.

The geographic distribution of the protests offers a clue as to just what has happened. The areas of the country that resisted the rise in the price of petroleum are precisely the areas that have benefited the most from government long-term developmental programs. The government has insisted that the protests are a conspiracy against the Islamic Republic, but our analysis shows that the Islamic Republic, through its long-term developmental and welfare programs, has empowered a citizenry that now resists neoliberal policies, such as cuts to energy subsidies. Our analysis further provides systematic support for the observation that Iran’s youth cohort has become a source of anti-government protest. As long as government does not address the needs and demands of this demographic, further unrest is possible.

TO VOTE OR TO PROTEST?

The supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, touts voting in the country’s elections as a means of demonstrating support for the Islamic Republic as a whole. For citizens, voting is also ostensibly one of the few available means of expressing one’s preferences and advancing one’s interests within the system. But like the citizens of other electoral authoritarian regimes, many Iranian voters debate whether voting really does offer them meaningful choices: whether, by voting for a moderate candidate in a particular election, they can help push the regime in a more democratic or liberal direction, or at least prevent hard-liners from consolidating control; or whether participating in elections only contributes to the regime’s claims for legitimacy.

For these reasons, voter turnout data and electoral choices seemed to us an appropriate mine to tap in understanding citizens’ attitudes toward the state. We used turnout in the 2017 presidential election to help determine the extent to which citizens in a particular county believe they can pursue their grievances and demands through the institutions of the Islamic Republic. Citizens who do not participate in elections most likely do not believe that the channels the regime offers can be effective for them. We found that the counties with lower rates of electoral participation were more likely to witness a day of protest. The average turnout in protesting counties was 13 percent less than in nonprotesting counties. We concluded that economic grievances were likelier to inspire protest in areas where frustration with the whole system was endemic. This finding could be interpreted to mean that economic hardship turned frustrations with the system into assertive protest activities.

The finding was all the more striking when we tried the same analysis for the last protest wave, in 2017–18. Electoral turnout was not a robust predictor of protest in a given county at that time. One possible reason for the difference is that the Internet played a significant role in spreading protest across the country in 2017–18, such that the protest map for that wave may not correspond with the map of political grievances. During this year’s wave of protest, however, the Internet was shut down. Only the depth and politicization of grievances could then spread the protest across the country.

For this year’s protests, we wanted to know not only whether participation in the election correlated with protest activity but also whether the choice of candidate, among those who did vote, could be mapped onto a county’s activism in a meaningful way. In 2017, President Hassan Rouhani was the reformist-backed candidate, running against Ebrahim Raisi, who was the main candidate of the hard-line faction. We found that counties that voted more heavily for Rouhani were more likely to witness a day of protest and counties with a higher Raisi vote were less so. Rouhani’s average vote in protesting cities was 59 percent, while his vote in nonprotesting cities was about 51 percent.

These results highlight an important dynamic in Iranian politics. For many citizens, voting for Rouhani was a pragmatic choice, not an indicator of a deeper belief in the regime’s legitimacy, as Khamenei likes to claim. Given the high incidence of protest in counties that voted decisively for the moderate candidate in 2017, we can surmise that some of these voters are disappointed with the outcome of their choice.

Rouhani’s campaign promises included many on which he has not delivered, such as pledges to introduce political reforms and improve the state of Iran’s economy. Some voters are perhaps so disappointed in the outcome of their effort to address problems through the electoral institutions of the regime that they have taken to the streets to manifest their anger and frustration. The violent repression of the protests is likely to intensify such feelings. Some of Rouhani’s reformist supporters have recently stated that this crackdown marks the end of electoral politics as usual in the Islamic Republic.

Courtesy of Mohammad Ali Kadivar

MAKING AN OPPOSITION

The price hikes that touched off the protests have proximate economic causes: U.S. sanctions, together with government mismanagement and corruption, have led to a serious economic contraction in Iran. But a deeper dynamic related to Iran’s long-term development may also have helped to make the fuel price increase so explosive.

The protests have taken place in the most developed parts of Iran. We measured the level of development in each county in terms of literacy rate, the percentage of college students, the number of public hospital beds per 1,000, and the percentage of households that receive electricity. That higher levels of development correlate strongly with a higher incidence of protest dovetails with an argument that has gained prominence in the study of development and social movements. Scholars have found that citizens in developmental states that invest in infrastructure, education, and health care are then empowered to demand greater political participation. When these states take a neoliberal turn and try to cut subsidies or privatize state enterprises, that empowered citizenry becomes the opposition against the state. Karl Marx once said that the bourgeoisie produces its own gravediggers. One can likewise say that developmental states make their own opposition.

Iran is a developmental state that has made a considerable investment in education, health care, and infrastructure nationwide. The counties that have experienced protests are among those whose development has benefited most from state support—and where people are therefore particularly likely to oppose its withdrawal, in the form of cuts to energy subsidies. Islamic Republic officials have called protesters “thugs” and depicted their mobilization across the country as a plot against the state directed from abroad. But our findings suggest that the Islamic Republic has itself empowered the citizens who now defy it on the streets.

The protests largely occurred in counties with large urban populations: the more populous the county, the likelier it was to have a day of protest in both the current wave and the one in 2017–18. This finding is not surprising, because critical masses of people can more easily form on the streets of larger cities. Also unsurprising is the fact that after controlling for the size of urban population in each county, we found a positive and significant effect for the size of the young male population between the ages of 15 and 25.

Social scientists speak of this effect as a youth bulge, meaning that disproportionally large youth cohorts make countries or localities susceptible to riots, civil wars, or criminal activities. The reason is that states have difficulty providing jobs and resources to very large young populations. Dissatisfied with the allocation of resources, these angry young men are prone to join urban riots, for example. The Islamic Republic has long struggled to provide jobs and opportunities for its young population. Our finding suggests that the frustration of this cohort contributed to this last wave of protest. Curiously, we do not find the same pattern for the 2017–18 protest wave—a finding that suggests the grievances of this cohort have been politicized and activated in the last two years.

THE NEXT WAVE

Today’s protests have arisen in places with some distinct, shared characteristics. They are developed, populous, and urbanized counties with large numbers of young men. And they are places where significant numbers of eligible voters either choose not to vote or vote for the moderate candidate. Such counties will likely remain at the forefront of oppositional political activity in Iran.

If it is true, as our findings suggest, that nonvoters and voters for moderate candidates have converged in resorting to street protests, then the repressive tactics that have met those protests will likely bring these groups closer still. In fact, artists, reformist politicians, and imprisoned leaders of the Green Movement, most of whom implicitly or explicitly supported moderate candidates in recent elections, have issued statements condemning government repression and demanding structural changes in Iranian politics. If such sentiments prevail among moderate voters and those who do not always vote, Iran could see a decline in turnout for parliamentary and presidential elections in 2021 and 2022.

The Islamic Republic has long relied on elections to gain support and legitimacy. But our results suggest that when nonelectoral institutions obstruct Iranian citizens from achieving the goals they pursued as voters, they may turn to protest instead. The regime has taken a heavy hand in response to the latest street actions. But repression will not address any of the factors that our analysis identified as contributing to this wave of protests, and so it is likely that a similar wave will rise in its wake.