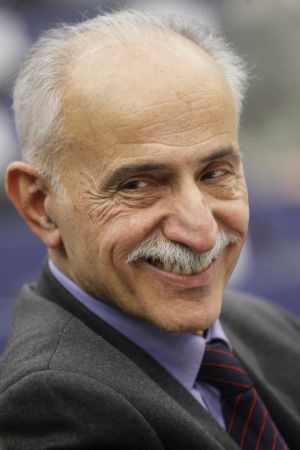

Dr. Karim Lahiji

8 March 2014 – The nuclear deal brokered by EU Diplomacy Chief Catherine Ashton in November 2013, who chaired the “P5+1” group (the UN Security Council five permanent members plus Germany), ended years of diplomatic stagnation between the international community and Iran. Fraught relations under the Ahmadinejad presidency left little to no space for EU diplomacy, and the international community’s primary attention on the nuclear issue led de facto to the overshadowing of the human rights agenda.

Now that constructive talks on the nuclear issue are progressing, the European Union can open talks on human rights and democracy and reengage with the founding values of the Union it has so strongly committed to use as a basis to all its foreign policies.

Catherine Ashton’s trip to Iran during the weekend weekend – the first visit of a High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs since 2008 –carries the prospect of a fresh start for EU-Iran relations. Ms. Ashton’s agenda however still appeared to revolve around the nuclear issue, including talks on uranium enrichment and the visit of Isfahan, one of the nuclear sites.

It was fundamental that Ms. Ashton wear not only her nuclear negotiator hat during her visit, but represent the voice of a resolute European diplomacy and place human rights at the centre of talks with President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Affairs Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif. Now, Ms. Ashton must build on the still fragile momentum of the nuclear deal to engage the Iranian authorities on tangible human rights commitments and address clear public messages to the Iranian population. At this moment of history, bypassing fundamental issues of human rights and democracy in the first EU high-level diplomatic contacts would set a deplorable starting point to renewed relations.

Expectations for an automatic improvement of the human rights situation in Iran with the election of Mr. Rouhani have so far not materialised. The UN General Assembly has continued denouncing, in December 2013, the “serious ongoing and recurring human rights violations” in the country. The number of executions in Iran has notably spiked since the taking of office by the new president – now over one hundred since the beginning of 2014. A significant number of human rights defenders, including lawyers, women’s rights defenders, trade unionists and activists working to protect ethnic and religious minorities, are still in a very precarious situation in Iran prisons.

At a time when European political and business leaders multiply visits to Iran, there is an imperious need for a clear vision and message from the Union. The specificity of the Iranian regime fosters conflicting interests and uses to its advantage both this absence of a strong united voice among its international counterparts and the prominence of the nuclear agenda over all others.

In this context, pragmatism is certainly not contradictory with the need to speak out. Ms. Ashton must on all occasions avoid being boxed in by talks on general principles and pursue the objective of obtaining tangible commitments from the Iranian authorities. Key priority issues remain the release and full rehabilitation of imprisoned human rights defenders and peaceful activists and an invitation for the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran and other UN Special Procedures.

These essential measures are initial stepping stones for a genuine dialogue. During their visit last December, Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) broached possible developments with the with Iranian authorities such as a visit by EU Special Representative for Human Rights Stavros Lambrinidis to discuss the terms of a human rights dialogue, the setting-up of an EU Special Representative for Iran, and the opening of an EU Delegation in the country.

The EU should work with Iran on the elaboration of these developments but must remain extremely careful not to reduce human rights discussions to issues of processes and institutions. The EU should strategise its approach to future relations with Iran by undertaking a thorough assessment of the current human rights situation in the country and develop indicators to measure progress and adapt its strategy accordingly – as set out in the EU Guidelines on human rights dialogues with third countries.

MEPs also evoked the need to work on tangible prospects for human rights improvements, like the apparent readiness of Iranian MPs and officials to work on diminishing the number of executions for drug-related crimes. Opportunities like this should of course be seized. But working on technical support to achieve tangible results must absolutely be integrated into a wider strategy. In her contacts with the Iranian authorities, Catherine Ashton should also reflect on lessons learnt from the latest period of opening with Iran, after the election of President Mohammad Khatami in 1997. Although a few years of talks allowed progress in several sectors like trade, investments and energy, no tangible result emerged from a human rights dialogue which existed in isolation and without any proper follow-up mechanism. A major mistake for the EU was to maintain, at all cost, an “open door” with the authorities without the support of a benchmarked strategy, instead of encouraging a progressive reinforcement of civil society participation and overview in the talks.

With this fresh opportunity, Catherine Ashton should insist in all instances on the inclusion of civil society in any future talks concerning human rights, but also regarding sectoral cooperation, with the ultimate aim of integrating this independent voice in EU-Iran talks at the highest level.

The EU cannot afford, a second time round, to lose contact with the Iranian people who nurture the hope that this regime’s opening to the world will lead to a better future. Reforming the Iranian regime is probably a mirage, but giving decisive support to the emergence of the Iranian civil society is not.

Karim Lahidji

President of FIDH

The International Federation for Human Rights